We're committed to helping you

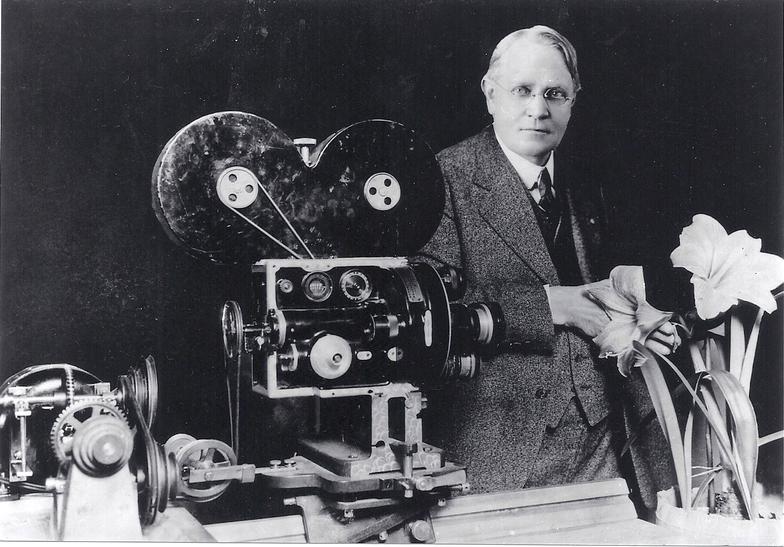

Arthur Clarence Pillsbury - 1870 - 1946

prints and provided dark rooms for rent. He needed

The Life's Work of Arthur C. Pillsbury

October 9, 1970 – March 5, 1946

A Short Biography

&

Listing of dates, events, and accomplishments

by Melinda Pillsbury-Foster

prints and provided dark rooms for rent. He needed to work; his family had two sons in college and could not offer him the luxury of focusing singly on his studies.

A. C.'s parents, Dr. Harlin Henry Pillsbury and Dr. Harriet Foster Pillsbury, had come to California from Brooklyn, where his mother had attended the Women's Infirmary in New York in pursuit of her career as a medical doctor. His father had studied medicine at Dartmouth and then at Harvard. Because of the failing health of their oldest child, a daughter, the family moved to California following the advice of Charles Nordhoff who had recommended it for those with extreme medical needs in his book, California for Health and Residence , written in 1870. The family took ship down the East Coast to Panama and then crossed the Isthmus on wagons and came up the West Coast to San Francisco in 1883. They settled in Auburn, California where Dr. Mrs. Pillsbury established a medical practice and the family built up their own fruit farm. Their daughter died there in 1894.

Their two sons, Ernest Sargent and Arthur Clarence, went to Normal School in Auburn and the family was active in the First Congregationalist Church there. While still a boy A. C. ran his own small business selling chickens of exotic varieties in Auburn.

Owning and running a business was therefore natural for him.

Time Line - Stanford Years from The Daily Palo Alto and other sources

It was at his business in Palo Alto that he sold the solio prints of the first Fraternity Rush at Stanford. He took the 60 shots in a period of one hour during that raucous event. His first visit to Yosemite took place the same year by bicycle from Palo Alto. In Yosemite, he signed the huge book, known as the Great Register maintained for tourists at the Cosmopolitan in Yosemite Village, then located between the Yosemite Chapel and the Sentinel Bridge. He had gotten the idea for the trip because an old acquaintance of his mother's Susan B. Anthony, made her last trip to Yosemite during her tour of California that year.

At A. C.'s business in Palo Alto he also built and sold bicycles and motorcycles. A. C. built the first motor cycle in California in the shop which was located in Palo Alto and became a disturbing influence on campus by driving it to classes. His shop was near the small private hospital run by his mother and father. Both he and his brother lived there at the hospital. At that point in time Stanford had a varsity team in bicycle and A. C. was a bicycle Letterman. His major was in Mechanical Engineering. His first invention, a slicer to produce specimens for microscopic slides, had been produced in 1894.

He proposed for his senior project in 1897 a design for a circuit panorama camera. His senior adviser told him not to build it because it was impossible.

Ignoring this advice, he built the camera. It worked. He quit school and took the camera to Alaska where he spent part of each of the next three years using it and conventional cameras to document the opening of the mining fields and towns in the Yukon. He took the camera set up, which was heavy, over White's Pass on a dog sled which he attached to his bicycle. He then traveled to the headwaters of the Yukon River and installed the cameras, a portable darkroom, and himself, in a canoe and took pictures documenting the many mining towns along that waterway and the development of the towns. His adventures and near misses with death are documented in news articles and in his partial autobiography.

After leaving the Yukon A. C. started a photographic business in Seattle and then settled briefly in Los Angeles, starting a business in the production and sale of photo postcards, panoramas, and prints. The took him all over California, and all of the adjacent states.

From 1903 until March of 1906 he was employed at a photojournalist for the San Francisco Chronicle. This was his only ordinary job.

In March of 1906 he founded the Pillsbury Picture Company. A month later he had used his circuit panorama camera to document the burning of San Francisco in the wake of the San Francisco Earthquake which shook him out of bed in the early morning hours of April 18th. His photos of this event went all over the world in the immediate wake of the disaster because he was the only photographer able to arrange for printing and shipping. In the face of difficulties insurmountable to most people he was resourceful and inventive.

Immediately afterward he used the proceeds from sales to achieve a long time desire to own a studio in Yosemite. He purchased the Studio of the Three Arrows that year and began operating the studio the next season. He had been visiting Yosemite since his first trip there in 1895 and had purchased a studio with Julius Boysen in 1897. But his new bride refused to live in the wilderness and left him. Distraught, he sold his interest to Boysen and went to Alaska on a boat he operated himself. Shipwrecked at Dixon Straits, he rescued himself and continued on his way.

For the next three years he spent part of each year in the Yukon photographing the opening of the Gold Fields and the building of the mining towns that are now a part of American history. His near escapes from death and adventures appeared in news articles both in San Francisco and places like Indiana.

Returning from Alaska he started a studio in Seattle, Washington for a brief period and then moved to Los Angeles to live near his parents and older brother, Dr. Ernest Sargent Pillsbury. There, he designed the solar heating system in his brother's home on what is now Hollywood Blvd. While in Los Angeles he started another business producing photo postcards and started writing articles for such publications as Camera Craft. The family remained close, getting together for most holidays. A.C.'s parents had retired and spent much of their time between their sons and other family members.

In 1903 he moved to San Francisco and went to work for the San Francisco Chronicle as a photojournalist; this was the same year he photographed the dynamic young president, Theodore Roosevelt, during the President's trip to Yosemite.

In March of 1906 he started the Pillsbury Picture Company. The next month he was shaken out of his bed in his home in Oakland by the first tremors of the San Francisco Earthquake. He was instantly on his way to the City with two cameras, one a graflax and the other his circuit panorama camera. During the next days and weeks he captured the City as it was consumed by fire and its people as they fought back against the forces of nature. He photographed relief measures and the amazing scenes enacted as San Franciscans began to rebuild.

The next month he married a widow who he had known when he was still in Normal School in Auburn, California. Her name was Ethel Banfield Deuel, but she later changed her first name to AEtheline. What began as a honeymoon tour of California became a working vacation where he spent most of his time traveling around the state, from San Diego upward, photographing all of the Missions in California and the beauties of the world around the Missions. He had been captured by an abiding interest in nature and the environment that would stay with him all of his life.

His interest in technology was unabated and his work as a photojournalist continued. Along with his older brother he would own the earliest of automobiles finally settling on Studebaker as the most mechanically reliable.

In 1908 the world was on the march. The president who A. C. had photographed standing in the Mariposa Grove next to the Grizzly Giant, had sent an enormous flotilla of ships, the strength of America's Navy, around the Horn on a tour that would take them around the world. The Great While Fleet, which it came to be called, had left from Hampton Roads December 16, 1907 and sailed south making stops at ports along the way. A. C. managed to get the most striking photos of the Fleet's entry into San Francisco. He had been retained by the Examiner and decided that the best location was from Pt. Bonita. He obtained permission from the Army officer in charge of the facility and was the only photographer to catch the fleet steaming in to the Golden Gate in perfect formation. In the northern channel nearest him the sky was overcast but the light perfect; his trusty panorama did its self proud. Other photographers were able to capture only one or two of the ships at a time; he caught them all in one shot. As the fleet steamed on by him., the gray fog settled down and the proud procession disappeared into it. Of the hundreds of images this would be the only one showing the entire fleet entering the Gate. It was so good the Examiner ran it full size 3 feet long across both pages.

A.C. had also arranged for panoramas to be taken on board the ships as they steamed up the coast past Baja California and on past the coast. These also sold well.

The rebuilding of San Francisco continued. In October of 1909 he decided to make a series of panoramas of the rebuilding from the air. To accomplish this he bought an aerial balloon which he named the Fairy because it was gossamer and white, and had it towed out to the harbor anchored to a tub boat. The day, October 31, was idyllic. There was no wind into far into the afternoon when suddenly a violent gale came up out of nowhere and drove the tugboat and the balloon carrying A. C. across the harbor.

The wind ripped the balloon from the ropes that held it to the tug and A. C., clinging to his photos, was jerked into the sky. Aeronauts were consulted and expressed the opinion that he could not survive. His death was reported in the afternoon papers. But despite being chilled to the bone he managed to bring the balloon down in the mudflats south of the City and made his way home to find his wife being interviewed by a reporter who reportedly fainted when she saw him. A. C. had managed to hold onto his film and the sales were fantastic.

The world of travel by air was just starting. This would not be A. C.'s only experience with photography and sky. In 1910 he was invited to take the Fairy to the First International Air Show held in January and photograph events from 500 feet up. This was the first air to air photography and A. C. also used the photos in the article he wrote for Sunset that year, titled, From One Aircraft to Another.

This same year, 1909, Arthur C. Pillsbury began showing the first nature movies ever to be filmed on the porch of the Studio of the Three Arrows in Yosemite. In Yosemite he had begun photographing the nature wonders of cliffs, stone, and waterfalls and also the small miracles of flowers as soon as he bought his studio. This was a natural outcome of owning a studio in Yosemite and his fascination with technology.

It was his desire to share the beauties of Yosemite with the world that lead him to experiment with lapse-time photography. He had been experimenting with lapse-time for a number of years, attempting to create a medium in film that allowed him to give the viewer a sense of the motion of clouds and water that held the attention of the viewer but did not seen unnatural when a circumstance in the Valley moved him to build the first lapse-time camera to record the blooming of flowers in 1912.

The wildflowers were disappearing from the meadows. His years as a photojournalist had showed him that images conveyed immediate powers of persuasion and he brought that force to bear on the Park Service. He produced and showed the first film of a flower blooming in 1912 and as soon as possible arranged a showing for those who could stop the mowing that was destroying more species of flowers every year. His approach worked and mowing the meadows became a thing of the past.

In his personal life many things had changed in the previous five years. He had become a father three times over. His older brother, Dr. Ernest Sargent Pillsbury, a physician specializing in reconstructive surgery, and his wife, Sylvia Ball Pillsbury, had been killed in an automobile accident while taking the children up to Santa Barbara on vacation on September 4, 1911. A. C. dropped everything else and went, meeting the kids, still in shock, in Ventura. The Auburn Six the family was driving went over a washed out embankment and down into the canyon below. Six weeks later A. C. went into court in Oakland and adopted them. All of them had been injured and ranged in age from 6 – 13. The youngest was A.C.'s godson and name sake as well. The two Arthurs shared a birthday party every year.

Yosemite became the family home for six months out of the year The kids left school before it closed in Oakland and Berkeley and did not return until after it had opened. Yosemite was very different then. Having children reorients us.

The number of tourists who went through the Park annually was low. The number reached a high of around 10,000 in 1905 and in the aftermath of the Earthquake plummeted to about half of that. Business was thin for all of the concessionaires. For A.C. this mattered less than for many of them. He had retained his business in San Francisco. His interest in technology was not academic; anything he learned or invented was immediately applied and used. For many years he watched for the development of reliable color film but was disappointed in the available technologies until Technicolor was made available by Kodak.

Images from that period were not only of Yosemite but from all over the west were cataloged for the Pillsbury Picture Company's stock during this period. Into the collection came a block of images that showed the kids growing up. These showed the growing compound that surrounded the Studio of the Three Arrows. All of the kids had friends who came with them in the summer to work at the studio. They worked together, explored Yosemite, and learned about the world of nature at the showings of films and lectures that began to be a regular feature of life at the Studio of the Three Arrows. There was a lot to do. Postcards needed to be produced, prints framed, items sold, the studio and compound needed to be cleaned, too. A. C. had begun producing specimen cards of wild flowers so that tourists could go into the meadows and find the flowers they had seen on the flickering screen. The cards came in a wooden box and were hand tinted. This was another job that needed to be done.

The first nature center had been born. But the screening room was the porch of the Studio and the work crew just out out childhood.

When you are raising children many things change. During this period A. C. focused on the studio in Yosemite. Business was picking up as the numbers of tourists increased. The kids loved the Valley, regarding it as their real home.

The focus of A. C.'s creativity found new outlets.

Along with the nature films that would soon be emulated by Hollywood for use as short features, A. C. undertook many projects that were immensely entertaining to his family. Among these were a series of stunts that allowed him to at one time acquire a new Studebaker and get photos that allowed him to sell most postcards. The potential for images to impact the public had become a familiar tool to be used to educate and to delight and surprise.

It was the kids fascination with Indians that first brought the idea to his mind. A cousin from New Hampshire who had worked with Plains Indians and studied their culture came to Yosemite during the summer of 1913 and encouraged the kids of the Studio of the Three Arrows to dress the part. This agenda was adopted with enthusiasm. After the initial burst of excitement something else happened. The kids continued their interest, inquiring into the customs, crafts, and living techniques of the Native Americans who had first lived in Yosemite. Indian themes became focused on those of the Miwok as the kids learned about the food preparation, weapons, and customs of those who had lived in the Valley before them. From this A. C. became aware that the Miwok had a problem. Their lives in the Valley had been marginalized and they were struggling to survive and care for their children.

This need evolved into Indian Field Days, an event put on in August that allowed the Miwok to sell their craft items, including baskets, to tourists and make an income.

Indian Field Days were an instant hit, Tourists came in to see the event and others lingered so as not to miss it. Competitions is such events as potato polo were part of the schedule.

The Indian themes were promoted at the Studio of the Three Arrows through the sale of booklets and other items that continued the Miwok theme and told the legends of the People of the Yosemite. One of these projects was a movie, titled legend of the Lost Arrow, an old Miwok folk story. A. C. filmed it using Don Tressidor in the title male role. Don had lost his job at Camp Curry for taking Mary Curry up the back of Half Dome. His work at the Studio of the Three Arrows allowed him to stay in the Valley for the summer of 1916 and continue his romance. The two were married in 1920 and A. C. photographed the wedding.

A. C. had more than one reason to focus his energies as he did from 1912 – 1924. While his brother had been wealthy none of the money came to the kids because of the rapacious court system who allowed a trustee to be named who looted the estate despite the protests of the family. A. C. had many extra expenses and no extra income to pay bills. So the Studio became economically important to A. C. and he began to focus on one of the themes that the Park Service was discussing constantly. How to get more people to come to Yosemite and use the Park. Odd as it seems today then there was barely enough income flowing in to keep the Park afloat. So A. C. became an arm of public relations and publicity that made him invaluable to the success of Yosemite, traveling throughout Northern California to speak to groups and show the films that were also shown at the Studio of the Three Arrows.

By using his films to publicize the majesty and beauty of Yosemite A. C. awakened the public to the desirability of conservation while at the same time helping the Park Service. More and more people heard from friends who had seen the films at a local garden club or school that the programs at the Studio of the Three Arrows were not to be missed. There, they learned about nature as it had never been presented before.

Concessionaires at this point in time paid a fee to do business in the Valley. A license to do business was issued every year and no concessionaire had any dependence on having a license issued for the next year no matter how much they had invested in building their shops and camp grounds.

Many concessionaires barely broke even at the end of the season. But because he served the public, giving them not just photos but products and resources that entertained while educating, A. C. became far and away the most successful photographer in the Valley. He noticed that many tourists would buy postcards instead of taking their own photos. So he sold small packs of smaller prints to accommodate their needs. A. C. also produced d'orotones, prints on glass painted with a gold backing, that tourists collected avidly. In 1924 A. C. produced one for a Hollywood producer who paid him $26,000.00 for the piece. Innovations were a constant at the Studio of The Three Arrows.

A. C. had a lively sense of adventure and a fey sense of humor and indulged these in ways that proved to be profitable. His 'stunts' helped spread the word but remained a self conscious means of achieving his larger goal, making the natural world real and visible to everyone.

The stunts were always entertaining. The Desmond Company had been given the right by the Park Service to run concessions within the Park and as part of their publicity campaign sponsored events. David Curry, competing with the Desmond Company, offered a cup for the first car into Yosemite. This is not difficult today but then the Valley could be snowed in and transportation by road impossible A. C. won the cup every year it was offered though the last year they had to give out two when A. C. had special flanges made for his Studebaker and drove in on the Railroad tracks. On his way out he met a man shoveling snow, determined to beat him. Another cup was made. This one said, “First Car into Yosemite by regular road.”

The Nineteen Teens were the years when A. C. experienced the fun of delighting his children with stories and events that would become legend.

1916 was an especially interesting year for the kids and for A. C. On April 10th of that year A. C. won the trophy for the first car into Yosemite traveling over the railroad ties. He had secured permission in advance from General Manager O.W. Lehmer, who also detailed F.L. Higgins, Superintendent of Motive Power, to accompany the party to render any assistance necessary and protect them against meeting trains. One of the four people traveling with them was a Studebaker agent from San Francisco. A. C. had been able to persuade the San Francisco outlet for the car company that the publicity was worth a new car. In this way he kept himself supplied with transportation for many years.

A. C.'s stationary carried this imprint: A MILE of motion pictures and colored views of Yosemite and the High Sierra SUMMER AND WINTER Sunshine and storm. Its towering waterfalls and cliffs its glaciers and lakes, giant trees and wold flowers. The climbing of Mr. Lyell and Half Dome, and many new waterfalls all reached for the first time with the motion camera. These views were shown before the National Geographic Society and the National Press Club in Washington D.C. and are endorsed by Franklin K. Lane, Secretary of the interior, and other prominent educators and public men. The Department of the Interior has granted me two years’ exclusive rights on the Indian Legends of Yosemite, now in course of production in a seven reel story.

Among his other activities A. C. was chairman of the Fourth of July celebration in Yosemite and this meant he had to coordinate a series of activities that involved chairmen of specific activities. These chairmen were frequently less than pleased at cooperating with each other; dominant egos abounded. But A. C. was able to accomplish this formidable task.

For the 4th of July A. C. planned a parade, creating categories for floats and other kinds of entries. That year the winner for the best float was the entry from the Studio of the Three Arrows. The entry was designed by his daughter, Grace, and included two of her friends and herself dressed up as different varieties of flowers blooming out of the meadow created from the interior of the car. The driver, the youngest son, Arthur F., was driving but was impossible to see for the greenery. Grace was a snow plant. The costumes were uncannily accurate.

The cables up the back of Half Dome needed to be replaced in July of 1915 and A. C. also headed that effort assisted by a group of 14, many of them students from Stanford University. The Ascent of Half Dome

This same summer he was photographing the building of the Glacier Point Hotel, which was finished, and of the Grizzly Hotel that never was finished. A. C., a methodical person, took pictures at regular intervals and when specific parts of the project were still in progress. The photo album that shows the progress is in the Yosemite Archives.

While he was going up to Glacier Point A. C. decided to emulate an earlier feat of daring, although he was far more cautions about how he did this.

A. C. arranged with some of the workmen to build a ramp out onto Overhanging Rock on September 17th and then winched the car out onto the stone, which hangs off the top of Glacier Point and was for many years just a few feet from the origin point for the Fire Fall. He then had the car slowly placed for a series of photo opportunities. Everyone and their brother climbed into and onto the car to have their presence there memorialized. A. C. himself sat on the hood. The afternoon was one of unblemished amusement. The car was emptied and the process reversed. The next day the photos appeared on the front pages of the San Francisco papers and before the end of the week A. C.'s life insurance had been canceled. He managed to get this reversed by showing the photos of how the car was placed.

The year of 1916 was a good one, but only one of a wonderful period of childhood his children would remember fondly all of their lives.

In 1919 A.C. arranged for an airplane to fly up from Central Valley and land in Yosemite. He went along, not for the ride but to take the first aerial photos of Yosemite. These, too were used at the Studio of the Three Arrows and for his lecture series. In 1921 he had a black and white film he had made tinted so that he could give viewers an idea what the colors of the flowers were. His focus was always showing nature in its full glory.

The years between 1912 and 1924 saw A. C. focused on what you expect a single father to be doing. His wife, AEtheline, had allowed A. C. to adopt the children but refused to be involved with raising them. She knew that would be time consuming and she had other priorities. Hence the agreement that the children would live in Yosemite for half the year. A. C. was raising his children as best as he knew how. Raising children means being there for them.

As the children grew up A. C. was able to spend more time on his lecture series. He also had time to think about how to deepen people's understanding of the physical world. For this project he found support in his nearby his home in Oakland. He was also ready to expand his operation in Yosemite Valley and was the first concessionaire to move to the new Village. The Pillsbury Studio was built there in 1924.

He had grown up using a microscope as an ordinary everyday tool. His parents had brought the first two microscopes to California. These had been used in their medical practice and for other research. He used a microscope himself for his work with plants, and said in his book, Picturing Miracles of Plant and Animal Life, written in 1937 and published by Lippincott and Lippencott, “watching the germination of seeds, the root growth and root hairs, the seed splitting open and the first leaves forming, the growth of the plant, the effect of geotropism on the growing plant and roots, the forming of the buds, their opening, the life of the blossom, its dropping off, petal by petal, and the pod growing behind it – all of this was of absorbing interest. .But with all of these visible steps pictured, the hidden mass of what happened in the pollen grain; just what growth means and how it is accomplished; the circulation of the sap; protoplasm and its movements; the nucleus; the chromosomes; and a host of other things, as the mingling of the nuclei and the forming of the new fertile seed; all remained hidden from the eye and camera lens.

Dead stained sections had been made of these microscopic life processes and still pictures made of them; but staining, which killed them, may have produced changes, not in life , and it could not be known, just how true they were to life conditions.

My first attempts to solve these mysteries were crude. I bought a binocular microscope of low power, thinking the camera lens could look into one eye piece while my eye at the other watched what was going on. This gave me up to twenty times magnification, not nearly enough except for small flowers, which I could photograph direct in the camera by similar methods.”

Dr. Harper Goodspeed, a professor of Botany from UC Berkeley, was in Yosemite at the time and the two talked. Dr. Goodspeed arranged for A. C. to use a laboratory that fall along with t he equipment usual to a laboratory. A. C. brought in his own equipment. He needed cameras and microscopes not available at Berkeley. He purchased in movie cameras and the best possible microscopes and continued to experiment. Other botanists and scientists viewing A. C.'s initial feet of film were not sure what they had seen; they had to think about it, analyze the meaning of the images that were confronting their eyes for the first time. The cost was high, and A. C. would buy equipment and then arrange for more lecture tours to pay for that equipment. But he had pierced a veil that had stopped human inquiry in many fields and could now summon up images that no human eye had ever beheld. Images instruct and enlighten and that was what A. C. was looking for. The Microscopic Motion Picture Camera

The photography did not remain focused on plants. There was a world out there to be explored and A. C. made it visible to all of us.

The research that resulted in the microscopic motion picture camera took A. C. from 1922 until 1927. By then he was using microscopic films in his lecture series, astounding scientists across the country. During the same time he had designed, built and patented a machine for mass producing postcards. This brought down his costs and took all production in house. His youngest son, Arthur F., ran the machine until he went off to Stanford himself to major in Civil Engineering.

In April of 1927 an article appeared in Sunset Magazine titled, A Motion Picture Director of Microbes. The article, with the use of pictures and text. The writer said this about the discovery, “Arthur Pillsbury has made on of the most important bacteriological discoveries of the age.

He has enabled the bacteriologist to study at leisure the smallest of life-destroying creatures, either in motion or at rest. Many bacteria move so rapidly that even the best of trained microscopists are unable to follow their motions, draw them clearly, or note their activities. Indeed, with many it is impossible to maintain the eye-strain necessary to observe them in the microscope. One of the greatest obstacles to to the study of communicable diseases has been this inability to become closely acquainted with the germ which caused the particular malady under investigation.

But Pillsbury realized that the eye of the camera never grows weary so he combined the two—or rather, three for he put in two microscopes, to give the camera a still better view of the microbes. With these two microscopes perfectly synchronized—and therein lies the secret of his discovery—he placed his bacteria actors on a glass slide, played a brilliant spotlight upon them and began to make motion pictures which have proved to be the surprise and delight of the world of scientists and physicians.”

The camera was a tool that enabled discoveries and cures; its uses would transform science.

A. C. did not patent his microscopic motion picture camera. This was not an oversight. Later in the same article the writer, having interviewed A. C., quotes him as saying, “I believe this discovery will be of inestimable value in bacteriology and probably will lead to much greater knowledge of communicable diseases, their cause, prevention and cure.” Said Pillsbury to the writer. Then he added: “This invention is to be dedicated to educational purposes. I could not think of even attempting to make money out of it. I will not commercialize it.”

The writer continues, “That is the attitude of the Californian who, saying he is not a scientist, yet has made one of the most important contributions to the science of medicine.”

But no one nominated A. C. for a Nobel Prize.

The world was moving towards groups of scientists working under the direction and funding of either government or large institutions, like universities. Many of those who used the tool A. C. created would be receive public recognition and some would receive the Nobel Prize. But A. C. had done this on his own working at the Studio in Yosemite and on his lecture tours to pay the bills. He was a modest man and not given to self promotion. Life had not been easy. He had become a father, raising children alone and without help, cared for his dying mother, and still run a business that allowed him to give to the world an unprecedented gift.

The Park Service, in recognition of his work for them had given him a contract that was longer than any other except for the Curry Company. A. C., cooperating with the Park Service's plans for development of the Valley, had been the first concessionaire to move his studio from what became known as the Old Village, between the Yosemite Chapel and Sentinel Bridge, and to the new location. There, he had born the cost for building a new Studio of the Three Arrows that included a huge movie theater so he could continue educating the public. There was even a cottage so that the family would not have to sleep in tents.

To achieve this while still working on the microscopic motion picture camera A. C. used up all of his savings and went into debt. He had every reason to believe this was the right thing to do. He had years of productivity left; the Studio of the Three Arrows was a profitable venture. His brother-in-law and son-in-law both invested in the Studio as well. They trusted him to make it work, he always had.

It was in a room he designed himself in the Studio that he had brought his immense collection of negatives. These were his bank account; the capital that made it possible for him to focus his attention on work that did not bring in a profit in dollars. A. C. was putting his time and money in an investment that helped humanity see its way through a critical period in the development of science; while it was looking for a direction that would determine many things.

In November of 1927 a fire started in the safe room and destroyed the entire working capital of Arthur C. Pillsbury. The collection of images is known now only by the numbers he used to identify and file them. Those numbers reach nearly to 100,000 distinct negatives. Included were the pictures of the children growing up in Yosemite, images of Yosemite and its wonders, more than taken by anyone else before or since. Stored there were A. C.'s images from all over California, Hawaii, Nevada, Washington, Oregon and places now known only because occasionally a post card or print surfaces in a collection and is identified. A small number of images where duplicated at his home in Oakland, but most were now gone.

Many men would have given up. One did. A. C.'s brother-in-law committed suicide, taking cyanide, unable to face the specter of debts that would not be paid off for more than a decade. A. C. dug in and got to work.

He no longer had the security of a profitable business in Yosemite. Many men would have rethought their decision not to patent their inventions. He did none of these things. He went on. The money from his lecture tour was used to pay debts. The lecture tour became his lifeline to survival. Even as they economized in every way possible A. C. did not give up his struggle to provide more ways for people to see the world.

In January 1929 edition of Popular Science an article on the work of A. C. Pillsbury appeared. This time he had invented the X-ray motion picture camera. In `his book, Picturing Miracles of Plant and Animal Life, A. C. outlines how he did this. He had been sitting in his seat on the train that was taking him to his next speaking engagement when he started to see how this could be done. He began making drawings and detailing the parts that would be needed. Arriving in New York he showed his drawings to a doctor who had spent thousands of dollars perfecting an X-ray camera for stills. The man pooh poohed the possibility of an X-ray motion picture camera. He had spent thousands of dollars perfecting his own just for stills.

Without money to continue his research A. C. looked for help and found it in the person of Dr, Coolridge at the General Electric Laboratories. A month later he had started building the camera he had envisioned on his Pullman car coming East to New York. In addition, he invented and patented that allowed him to do away with the perforations in film so he could set and draw the film a measured distance, stop it and repeat the operation as often as he wanted.

He had his camera. The first subject was a rose bud opening. He and Dr. Goodspeed undertook a series of experiments on the effect of X-rays on plants but this could not continue; A. C. did not have the money to pay for the equipment needed.

He continued lecturing and his work to deepen human understanding through photography took a different direction, one that took him to Pago-Pago in 1930. With him he took the first underwater camera, developed at his home in Oakland.

The underwater motion picture camera was less expensive to develop than the previous cameras had been. A. C. had begun work on the camera while dealing with the aftermath of the fire in Yosemite. He needed to find something to think about that took him away from those tragic events. Again, the film produced was used in his lecture series. He again did not patent the invention. Disney patented an underwater camera in 1943, over a decade later.

America was a different place in the 1930s. The Depression had dried up the market for speakers and although A. C. was still in demand he had to work hard to develop new material for his lectures. Unable to spend money developing new cameras he turned to developments of interest to the public he thought should be known, A. C. looked for areas and projects he could afford to do that allowed him to continue his work to increase the scope of our vision. One was a stereoscopic or traveling camera that showed in natural color thee sides of the same object as it passed by. He had also anticipated the technology of the film industry by decades by taking a film showing a cell pulsing and superimposing himself inside the cell lecturing. Special effects had been introduced. But it was not enough to fulfill the depth and breadth of his desire to make the world visible to others. He looked for other projects that used photography. One of these was the work in hydroponics taking place near his home in Oakland.

In his book, Picturing Miracles of Plant and Animal Life, the last chapter is Chemical Farming.

Chemical engineering had been known and used since Babylon still stood as a city. It had been applied many times in the course of human history. But in the mid 1930s a professor at UC Berkeley, Dr. William Fredrick Gericke, was involved in a series of experiments that would bring a long established practice into the modern world as a tool to improve the production of food. Americans were confronting the issue of hunger in a very immediate way and so this was a natural subject for A. C. to take up. He did his own experiments and filmed the results of those and of the work of Dr. W. Gericke and included the subject as part of his lecture series.

After the publishing of his book in 1937 A. C. continued his lecture series. He added to his films from trips to Jamaica and across the country. He introduced his audiences to the habits of insects, narrating their lives and using current events to make these relevant. But he was never again able to do the work for which he was so well suited.

However, these years tell us something very important about him, his character and his convictions. He paid off his debts without complaint. When he could not make a living from his lecture series because of failing health, savings exhausted, he went to work at UC Berkeley as a lab assistant. He remained cheerful, kind, loving towards his wife and children, and hard working to the very last day. He was far from perfect. All of his life he had been too trusting, willing to take people at their word. But how we see others reflects many of the truths about ourselves. A. C. was a person who could be trusted. Therefore he gave trust.

He died in the hospital in Oakland on March 5, 1946. In the aftermath of his death his wife, always distant from the three children, sold the remaining collection of his work that had been promised to Arthur F. for $100.00. She was selling the grandfather clock that had been in the family for over 200 years when Arthur F. arrived for the funeral. She chose to bury her husband of forty years in the Chapel of the Chimes but when she followed him into death two years later she had arranged to be buried elsewhere.

A. C. was remembered and his work was valued. Today his work continues to be among the most collected of all of the Yosemite photographers. His images, often uncredited, have become a part of our common heritage. It is a legacy that matters.

Arthur C. Pillsbury was a renaissance man whose accomplishments were overlooked, perhaps because their scope and immensity were difficult for most people to comprehend. The films, science, and direction of the Twentieth Century owe much to the tools that increased the depth and scope of vision that he provided. Next time you see one of his images on a post card or a print; if you use one of his inventions or view a film that uses his tools, remember him. He was an individual who chose to made a difference and accomplished his goal.

Time Line for Arthur C. Pillsbury

Arthur C. Pillsbury with his Lapse-Time Camera